Strategies to prevent or catch cancer early need to be delivered equally and respectfully to Indigenous communities in Ontario: researchers

In February 2019, Alethea Kewayosh, director of the Indigenous Cancer Control Unit at Cancer Care Ontario (CCO), attended a conference of Indigenous health workers. She led two workshops, presenting on the efforts of CCO to address Indigenous cancer care. Before she began, she asked participants, who were sitting at 10 different tables, to share the first words they thought of when they contemplated cancer.

“I called on the first table, and the first word that came to mind was ‘death.’ I went to the next table—‘fear.’ Then, ‘hopelessness,’ ‘sadness,’ ‘loss’ and ‘pain.’ There was not one positive word,” she recalls.

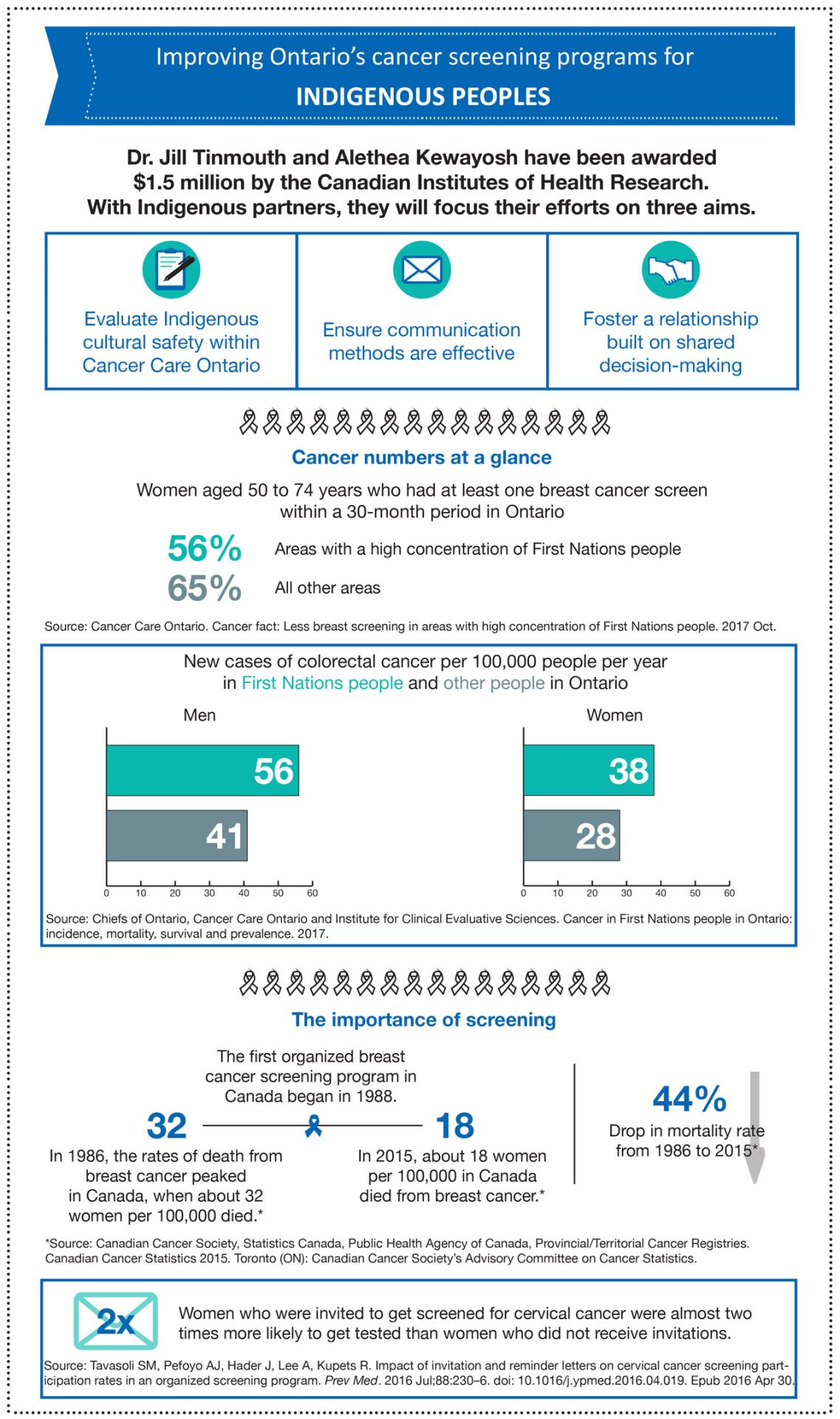

With a five-year grant worth $1.5 million from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Kewayosh and Dr. Jill Tinmouth, a scientist in the Odette Cancer Research Program at Sunnybrook Research Institute (SRI), aim to reverse these negative associations. Further, they intend to boost low screening participation among Indigenous peoples, thereby slowing the rise at which some in these communities are developing cancer. Evidence shows new cases of colorectal cancer among First Nations peoples in Ontario are at least 10% higher than that of other Ontarians, for example, and almost 10% more Métis women in Ontario are overdue for colorectal cancer screening compared with other women in the province.

Screening programs, which inform people about the importance of tests and invite them to participate to catch cancer in its earliest—and most treatable—stages, exist in Ontario for breast, cervical and colorectal cancers. “Screening is a good tool—studies have shown that it can reduce the incidence of cancer and deaths caused by cancer,” says Tinmouth, who is also a physician at Sunnybrook and an associate professor at the University of Toronto.

“I’m hoping that we start to see improved understanding of the screening programs by Indigenous communities, and I’m hoping we start to see more receptivity to participating in the three screening programs,” says Kewayosh, who is First Nations.

The pair’s project builds on research they started five years ago, thanks to another CIHR grant. “That work helped us to understand some of the issues faced by Indigenous persons in terms of accessing cancer screening. The biggest ones identified were poor communication, lack of trust and power imbalances between Indigenous patients and their providers,” Tinmouth says. “These issues lead to cancer screening disparities, and when [people] can’t access the system or have a poor experience with it, they’re less likely to be screened.”

As Kewayosh thinks back to the days when she and Tinmouth began collaborating on their first CIHR grant, she says, “Many communities were not aware of the screening programs. They were not aware of the importance of screening. They weren’t sure where you went to get screened, because it’s not like they can jump in a car and go down the street to find a screening program.”

To expand on their findings and improve the cancer screening experience of Indigenous peoples, Tinmouth and Kewayosh developed a program of research, consisting of three projects that are linked by the aim of improving cultural safety of the cancer screening system. The pair has assembled a team of researchers from CCO, Northern Ontario School of Medicine and U of T to lead these projects. Within U of T, it’s the Waakebiness-Bryce Institute for Indigenous Health and the Institute for Health Policy, Management and Evaluation that are involved.

Before explaining cultural safety, Tinmouth mentions cultural competency. It is having the skills, knowledge and attitudes to deliver a health care service in a way that’s effective and respectful to a specific group. Cultural safety takes it further: “Cultural safety puts the onus on the provider to be self-reflective and to have humility about the power differential that exists within our system, most often between providers and participants. The goal is to empower the recipient of care within the delivery of that service,” she says. “An important component of cultural safety is that the participant makes the determination about whether a practice or situation is actually a culturally safe one.”

Ensuring the system respects diversity

To improve Indigenous cultural safety in cancer screening programs for Ontario’s Indigenous peoples, the team will assess CCO’s current practices and then offer recommendations. Tinmouth says Indigenous points of view should be key considerations. “If you’re thinking about how to make something work and what policies to put in place for the cancer screening programs, your work needs to be informed by the perspectives and needs of Indigenous persons. That extends from the person who’s writing the policy, to the person writing cheques, to the people doing the cancer data analysis and the executives who are making the final decisions. There’s a need to look at the organization as a whole with that lens.”

Kewayosh weighs in. “When folks were developing [screening programs], they did not have an understanding of the Indigenous community and did not realize there were communities out there where it’s a lot more of a challenge to participate in screening,” she says. “My job is to ensure [Indigenous peoples] are comfortable with the process, and have a full and equal say in the work. What we do will be led and directed by the communities we work with. There’s no point in developing a program if they’re not going to have a very strong voice.”

Tailoring communications to connect better with people

Their second aim centres on communication. In Ontario, information about screenings is distributed via mail. A 2016 study in Ontario found that women who were sent invitations for a cervical cancer screening were almost two times more likely to get tested than those women who did not receive an invitation. It’s evident that these letters are beneficial in driving up screening participation, and therefore catching cancer at the earliest possible point, but how the information in these letters is presented matters.

Kewayosh illuminates the significance of clear communication when she shares the experience of many Indigenous peoples upon receiving a cancer screening notification by mail. Many people are unsettled—they don’t know why CCO is recommending a screening, and many misinterpret a screening notification as a cancer diagnosis. “These letters are really just to alert people that they’re due for a screen, but we need to make sure the communications are more sensitive and relevant to the audience to which they’re intended. A huge part of getting screening participation rates up is letting people know they’re due for a screen,” Kewayosh says.

Tinmouth chimes in. “Our current communication strategy is really geared toward a general audience and does not take an Indigenous perspective,” she says. She asks whether letters are the best vehicles for communicating about cancer screenings to Indigenous persons, and, if they are, suggests perhaps they should come from a community health representative or Elder. “We need to go through a process to understand who the best person is for these letters to come from.”

Supporting participants’ choices to make sound judgments

Another of their goals is to establish shared decision-making. Kewayosh says, “We want the individual to start having the control. It’s about increasing their understanding and putting them in the driver’s seat so they can make the decisions.” She underscores the idea that a screening isn’t something that is done to a person, but rather something a person opts to participate in willingly.

“Shared decision-making is about trying to make sure there is communication between the provider and participant, and that there is an exchange of information around the potential benefits and/or harms of screening,” Tinmouth says.

Building excitement and laying down the foundation for future endeavours

Given their aims are “ambitious,” as Tinmouth says, bumps in the road are expected. One of these is coordinating the many moving parts in the research program across each of the three projects. From the Indigenous partners to the CCO members on board, organizing the teams is a challenge Tinmouth anticipates, but one she sees value in. “The exciting thing is that CIHR, CCO and all of our various partners see the need for this and are ready to sit at the table, pull up their sleeves and get the work done.”

Tinmouth also looks forward to another opportunity the grant will facilitate. Embedded in the budget are resources to train students who aspire to be Indigenous scholars, and to hire and train researchers within the Indigenous communities in which this work is grounded.

Where they’ll be at the end of their five-year project is difficult to predict, but Kewayosh is confident their work will breed other efforts like it. “I think this is going to be that pebble on the pond, where things start to grow and take on a life of their own,” she says. Speaking about her motivation, she adds: “I believe we’re all given gifts, and we’re all supposed to contribute in some way, from whatever little corner of the world we’re in, to help make things better. As an Indigenous person myself, I’ve always been driven by the need to help make things better for my people.

“I’ve been doing this sort of work for over 35 years, so I’ve seen a lot. I see how having all of these health issues has devastated our communities. Every time I go to a community, even my own, I see how many people, at younger and younger ages, we’ve lost to treatable cancers. If folks were participating in screening so these cancers were caught early, we wouldn’t be losing our people. To me, it’s senseless. I have an opportunity to help improve that, and that’s what drives me.”

For Tinmouth, it’s about delivering care that meets the patients’ needs. “[This work is] something I’m very passionate about. I believe everyone who lives in Ontario should ideally have access to the same high quality health care, and should get that health care in a way that is comfortable, respectful and meaningful to them,” she says.

Looking back at the February 2019 meeting she attended and the bleak words participants called to mind when they thought about cancer, Kewayosh says, “I would like to see that change. One day, I’d like to go back to those tables and hear words like ‘hope’ and ‘survivorship’ and ‘better health.’”

This article was originally published on April 4, 2019 by Matthew Pariselli, Sunnybrook Research Institute.