Long lags in the testing of street drugs and the heightened risk of overdoses and deaths among users exposed to tainted drugs amid North America’s unprecedented opioid crisis, are the target of a groundbreaking partnership between researchers at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa that is piloting the use of a portable mass spectrometer to test drug samples at the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre (SHCHC) supervised injection site.

Long lags in the testing of street drugs and the heightened risk of overdoses and deaths among users exposed to tainted drugs amid North America’s unprecedented opioid crisis, are the target of a groundbreaking partnership between researchers at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa that is piloting the use of a portable mass spectrometer to test drug samples at the Sandy Hill Community Health Centre (SHCHC) supervised injection site.

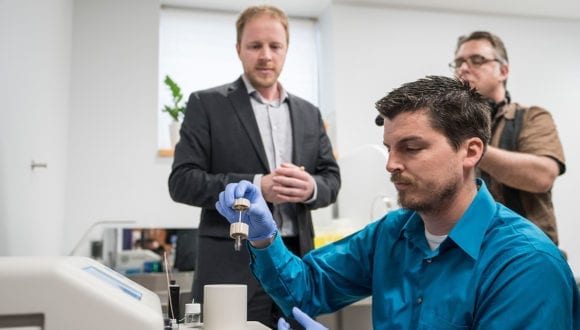

The 22-pound bread maker-sized machine, the first of its kind, can provide the precise “chemical signature” of a substance based on the mass of its constituent molecules, in less than 20 seconds.

In other words, it can rapidly reveal exactly what is in a drug from a trace sample no larger than a single drop of liquid. And nobody else in the world is using this technology in this way.

Clients who come to the injection site just off Rideau Street will be asked if they want their drugs checked before they use — and will be told exactly what’s in their syringe.

If it contains fentanyl or carfentanil, or another dangerous substance, including slightly modified opioid analogues, this information could convince them not to shoot up or prompt health centre staff to be on standby with naloxone for a potential overdose. And if testing exposes a pattern of bad drugs circulating through the city, officials can quickly distribute a widespread alert.

“This is potentially the most impactful research I’ve ever been involved with,” says Carleton Chemistry Prof. Jeff Smith, director of the Carleton Mass Spectrometry Centre (CMSC), who is helming the technology part of the project in collaboration with principal investigator Lynne Leonard from the University of Ottawa’s School of Epidemiology and Public Health.

“This is an opportunity to bring together analytical chemistry and an extremely pertinent social science question,” continues Smith, “and could lead to significant insights into how to address the opioid crisis. This is one of the things we can do as scientists — we try to help figure out the most effective way to address a problem.”

Leonard and Smith’s project, which is supported by $500,000 over three years from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, could lead to mass spectrometry testing at more locations in Canada, and at the same time it is gathering information that could drive policy change.

“This is something that’s really needed,” says Leonard. “It’s the right intervention at the right time.”

More work remains to be done to develop and refine the methods used to determine not only what substances but also how much of each substance are in the samples being tested, which is “one of the hurdles of any new technology,” says Smith, “because there’s no existing literature to follow.”

But all project participants are optimistic that it will have an immediate — and potentially profound — impact.

“We anticipate that people may adjust their behaviour based on what’s in their drugs,” says Boyd. “People in the community are angry and afraid because they’re seeing so many deaths.”

“In this end, this will save lives,” says Christine Lalonde, a member of the SHCHC’s community advisory committee, which was tasked with finding out what people in Ottawa’s drug user communities think about this project. “We don’t have two months if there’s a bad batch of drugs going around the city.”